Black On Which Side

A lifetime of searching for my place in the Black community has led me to ask questions about how I should participate in the Black Lives Matter movement.

Identity is complicated; a constant tug-of-war between your presentation of self and the impositions of a society insistent on categorization. Unfortunately, we are mounds of wet clay before we are sculptors of our own destiny. Self-awareness manifests after years of conditioning, leaving us to unlearn ingrained behaviors and prejudices once we reach our formative years.

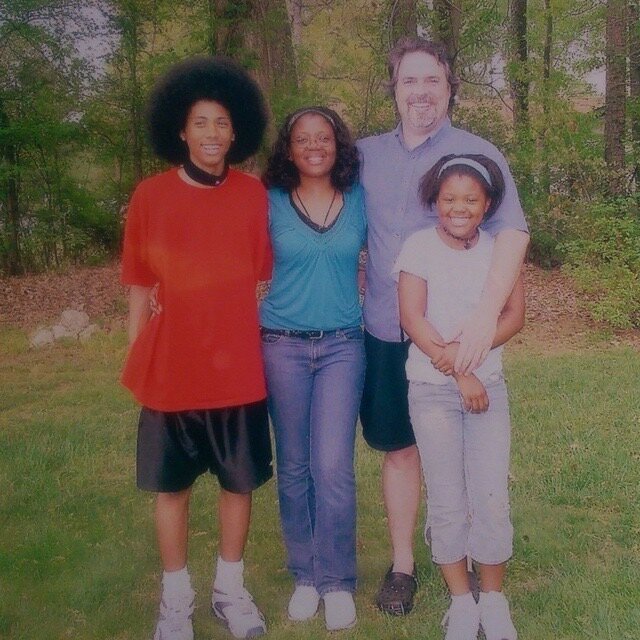

These are some of my categorizations: I was born in Durham, North Carolina, a Blue bubble in a Red Southern state, to a middle-class family, White father, Black mother; Raised in an upper-middle-class White neighborhood with White friends. My brothers; Attended an HBCU right out of high school (hated it), and graduated from a different HBCU 10 years later, my father’s alma mater (loved it); I enjoyed listening to hip-hop, playing basketball, and rocked a giant afro complete with the Black Power fist afro pick for most of my childhood — but my hip-hop was alternative and I never rapped the N-word, my skill was jump shooting (earning me the nickname “J-Wet” from now-mayor Steve Schewel), and my hair was untamable.

My self-identity was constructed by these building blocks but I never considered how they reflected my racial representation. There were times when I thought being mixed race was a superpower; the best of both worlds. I could walk between them like a chameleon, examining the intricacies of White and Black America from up close. As I got older, it felt like a curse at times, being surrounded by White people but not quite being “one of them,” and having little to show for as far as a Black community aside from my family.

Mostly, I just didn’t care. My friends accepted me for who I was. My family loved me unconditionally. Why did I need to qualify it any other way?

Growing up in a White neighborhood had its privileges. Safety was rarely an issue. We spent countless hours getting into all types of shenanigans (that I will happily share in a more intimate setting i.e. where my parents can’t read it) under the protective veil of Watts-Hillandale’s reputation. The neighborhood was filled with doctors, lawyers, professors, and future mayors. Interactions with the police were over traffic violations or noise complaints, usually ending in a warning and stern talking to. Compare this with Walltown, a neighborhood only separated by one (Broad) street but might as well have been the Elephant Graveyard in the eyes of both citizens and the police.

Before we moved into Watts-Hillandale, my family lived on Underwood Avenue in the West End, a neighborhood pinched between the recently-transformed Chapel Hill Street block that includes The Cookery, Grub, and Durham Co-Op, and the Lakewood Shopping Center, home of the Scrap Exchange and Cocoa Cinnamon. My two memories of living in that house are biting the tip of my tongue off jumping into the community pool and watching a group of men, wielding guns as tall as the violin I was practicing, harassing a woman walking her dog down our street. Needless to say, our stint in the West End didn’t last much longer but that story always reminds me of how fortunate I was to never witness violence like that again as a child.

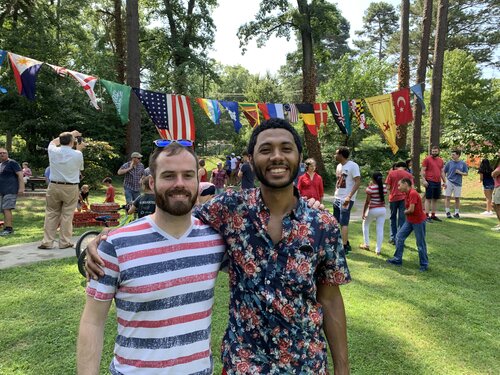

Insulation from the trauma of Black America didn’t mean I escaped trauma elsewhere. In 2008, my parents got divorced at the start of my senior year of high school. I lost my family unit, one of the few parts of my identity that felt concrete, during the most formative time of my life to-date. The isolation made me reckless, seeking acceptance through actions and people that did more harm than good. I was drinking at school because I knew my grades weren’t good enough to get into my college of choice. Because of the divorce, we had to move out of the neighborhood. But as always, my community in Watts-Hillandale lifted me up when I needed them most. John Barber, and his parents Tom and Shannon, invited me to live out the remainder of my senior year in their guest bedroom. Looking back, I'm certain I would have hit rock bottom without them. My parents did the best they could but I was stubborn and persistent in my quest to self-destruct.

John & Justin (& Diana) in the summer of 2008. Yikes.

John & Justin in the summer of 2019. Cellphone cameras have really improved.

Eventually, I found myself at Winston-Salem State University, the only school that would accept me. Being there felt like a failure. I thought I was smarter than everyone and I held it against them: my peers, my professors, and the entire institution. An institution filled with Black people. We could have helped one another understand the nuances of Black identity. Instead, it was just another identity crisis. My interests and the way I talked earned me the nickname “Kevin Federline” aka “token White guy” among my friend group. Acceptance was important to me in this foreign land. I hated the nickname. I let it slide.

The only saving grace from my one semester in Winston-Salem was being on campus Nov. 4, 2008. There is no other feeling like being surrounded by hundreds of other Black people on an HBCU campus celebrating the election of the first Black president. For one night, my version of Black felt acceptable. Barack Obama‘s mixed-race heritage allowed me to find peace in my own history. “The first Black president has white grandparents just like me.”

I didn’t come back to Winston-Salem in January.

Two years later, I enrolled at Durham Tech after spending 2009 “finding myself,” meaning trips up north to visit Sammy at Brown University for an indeterminate amount of time. What did I have to get back to?

Have you ever been to a community college? My expectation, like every other ignorant high school senior, was that community college was for flunkies. If you weren’t smart enough to get into “real” college, you were relegated to community college and destined for middle management at your local Advanced Auto Parts. If I knew then that Durham Tech was actually the embodiment of Durham culture and its values, filled with a diversity of people and intellectual curiosity, I could have avoided the Winston-Salem State debacle altogether. A person was not branded by who they were coming in but who they wanted to be when they left. Mothers, career professionals looking for a new passion, Early College high schoolers, immigrants who couldn’t afford out-of-state tuition at the universities, slackers, athletes who needed to get their GPA up to play collegiate ball, learning enthusiasts, everyone else, and me.

By this point, the afro was gone and my fitted hat collection was expanding. One of the first hats I bought was a red Philadelphia Phillies cap with white accents from Lids in Northgate Mall. Not only had I never seen a Phillies game in my life, but I rarely watched baseball, period. It was pure coincidence that I wore that specific hat into the first day of Spanish class and sat two seats in front of Adeel, a Pakistani immigrant from Philly, who was wearing the exact same hat. He expected to find another Illadelphian who identified with his roots in the Brotherly Love, but instead, he found a poser who had never stepped foot in Philadelphia or Pakistan for that matter. Still, Adeel accepted me into his orbit and introduced me to his friends, a group of other Muslim immigrants from the Middle East and Northern Africa. They welcomed me with open arms, tolerating my ignorant questions about Islam, calling me “Mr. President” because of my political ramblings, even throwing me a surprise birthday party. But I couldn’t help feel like an outsider when they would slip away to pray or bemoan the hunger pains of Ramadan. Islam rooted their identity in a tangible way.

My association with this new group of friends also made me rethink how I responded to questions about race, particularly on official documents. Could I call myself an African-American when I was surrounded by actual Americans of African descent? Black American didn’t tell the whole story either. “Two or more races.” That was my only option. Simply “American” was not.

American Literature II was my gateway drug into writing. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were my dealers. The murder of Trayvon Martin was my first long drag. His gut-wrenching story, along with Civil Disobedience, inspired me to start my first blog and move away from long rants on my Facebook wall. Trayvon Martin is a name in a long list of victims on the wrong side of racial violence but the first to capture the attention of my generation in a way I hadn’t witnessed before. The consequences of being Black in America were made apparent. As someone who has struggled with his Black identity for his entire life, I always find it unusual that this case is the spark that ignited my passion for writing.

Five years later, I graduated from North Carolina Central University, the historically Black college that my White father graduated from, with a degree in journalism. Even after all this time, I hadn’t come to terms with what it meant to be Black. Did going to an HBCU make me any more or less qualified to speak about the Black experience? I never attend 10:40 break in The Pit, a football game, or homecoming concert. I was too busy running a streetwear company with my multiracial Asian friend. Streetwear is Black, right?

In December, I experienced my first panic attack (which I documented here). A decade of suppressed anxiety finally surfaced, leading me to seek therapy. Quarantine has been a blessing in disguise. The time off has given me space to heal deep wounds that the rat race of American life does not permit, and to read a number of books including Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, an eye-opening letter from Coates to his son but also to anyone who is unaware of the substantial adversity faced by Black America.

Two days before protests erupted, I made dinner for my mom to entice/coerce her into having a much-needed conversation. It was the result of six months of counseling. I woke up the next day like Buddha reaching Enlightenment. 24 hours later, reality sank back in. George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis. The uproar around the country set off a new level of tension between the government and the populace already spurred on by the mismanagement of COVID-19. As messages flooded in and my social feed overflowed with #BlackLivesMatter content, my instinct was to ignore them. No black squares, no protests. I just worked through 10 years of my own trauma! Why would I subject myself to extreme anxiety all over again? Then I thought, “Black America has been subjected to extreme anxiety for hundreds of years. Am I being selfish? Had I failed them?”

One of the beautiful results of the moment has been the uplifting of Black artists and Black voices. “Wait a minute! I have work to share. I have stories to tell.” I hesitated. Was this moment really for me? Because I haven't (overtly) felt the prejudices of being Black, I have a hard time accepting the privilege of being Black when it's time for the come up. “Why is my Black any different from your Black? Had Black America failed me?”

Identity is not one-size-fits-all. My Black is not your Black, but Black all the same.

I was called to writing to empower others to find their voice while I searched for my own. Perspective is the bridge to understanding. I used to think that by not focusing on race, I was somehow light years ahead of the conversation. But our privilege and prejudice are unavoidable threads of our stories. Whether we choose to acknowledge how they shape our lives is left to us.